I have explained why I chose veterinary medicine, so I suppose it’s only fair to explain how.

For most of my classmates, including myself, the desire to become a veterinarian began long before I knew how to spell the word ‘veterinarian’. We volunteered at shelters or barns, showed our dog/horse/cat/calf/rabbit/goose at the county fair, and hung on every word the vet said when he came out to gavage our colicky horse with mineral oil. Many of us began agonizing over grades at a young age – after all, how could we possibly get into vet school if we failed that geography quiz in the sixth grade? We pursued work in related fields – research, cleaning kennels, working on farms, walking dogs, scooping poop. For others, the dream was born later, and adequate animal and veterinary experience was acquired with a fervor that might actually make the rest of us look lazy by comparison. Eventually, our hard work paid off, and the admissions committee at one (or more) of the thirty veterinary schools in the United States decided that we would make good candidates for a DVM. After four years of intensive training, of course.

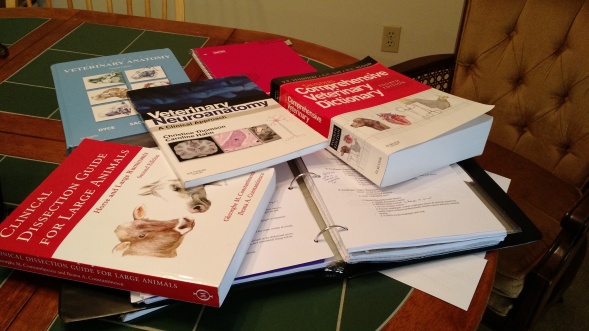

Four years. At Missouri, two years are dedicated to lecture-style teaching, and two years are dedicated to clinical rotations to give us the maximum amount of experience possible in the short period of time we are in school; since I actually know relatively little about the clinical rotations period, I’ll focus on the lecture half of veterinary school. While in school, we study the anatomy, physiology, microanatomy (histology, or the study of tissues), developmental anatomy, nutrition, and handling practices of: dogs, cats, horses, cattle, swine, goats, sheep, alpacas, birds, reptiles, and pocket pets (rabbits, gerbils, rats, mice, and guinea pigs). We also study epidemiology, radiology, endocrinology, bacteriology, virology, anesthesiology, pharmacology, toxicology, surgery, theriogenology, ophthalmology, business management, neurology, immunology, principles in public health, parasitology, pathology, emergency critical care, and various deviations thereof.

For every piece of information we learn, we also learn the species differences – cats require the amino acid taurine in their diet, but dogs do not (don’t feed your cats dog food!), and administration of a drug that is cleared by the kidney may be done in a cat’s hind limb, but it would never make it to the target organ if you gave it in a bird’s leg due to the differences in vascular organization. Sometimes, we even learn the human or primate equivalent – because knowing the typical cardiac pathologies of dogs and cats isn’t enough information! Eventually, we will begin to branch out and explore specific areas of medicine – exotics, orthopedic surgery, oncology – and focus our studies on one area. For now, though, we exist in a nebulous cloud of knowledge that pertains to one or several or all species, and we wait for the day we can apply it.